Sensuous Matters

I have by no means become an expert when it comes to conducting sensory analysis of olive oils, far from it, perhaps only developed a brief understanding for the complexity with which such knowledge is concerned, for it is namely, such as so eloquently framed by the work of Monteleone and Langstaff (2014), an entire science in and of itself. Not just that, it is one highly regulated and specified. Likewise, one in requirement of proper and, at times, quite extensive schooling and practice, and this not only with regards to the level of taster that one aspires to become, but also with regards to ongoing participations in descriptive sensory analysis panels whereby one, if selected by a panel head to participate in a particular evaluation, becomes subjected to the calibrated consensus with other tasters that is befitted for evaluations to be properly executed (Peri 2014: 41, 53). Tasting olive oils thus occurs a complex subject indeed. As a matter of fact, to become a certified olive oil taster and master the skills of organoleptic evaluation of so called positive and negative attributes of olive oils (Peri 2014: 35-40), even for the most basic level, one ought to undergo rigid and continuous practice, fulfill specific requirements, pass technical trials, be adept in terms of terminologies and descriptors as well as with scale rating systems and scorecards, develop particular knowledge about procedures of assessing profiles and qualities, and keep up with standards and regulations such as devised by specific manuals, for example by the International Olive Council (2021). One must, too, cultivate standardized reference frames to enable descriptive analysis of principal components and specified attributes. Phew, there is quite a hefty catalogue to master; if only the one requirement to be fulfilled had been that tasters must be “users of extra-virgin olive oil” (Peri 2014: 53), then I would be an eminent candidate for the job with my roughly 2 dl consumption a day. Not joking, seriously. But it is not, and I am despite my vast consumption of extra virgin olive oil, quite limited when it comes to making sensory analysis thereof; according to regulatory qualifications and otherwise.

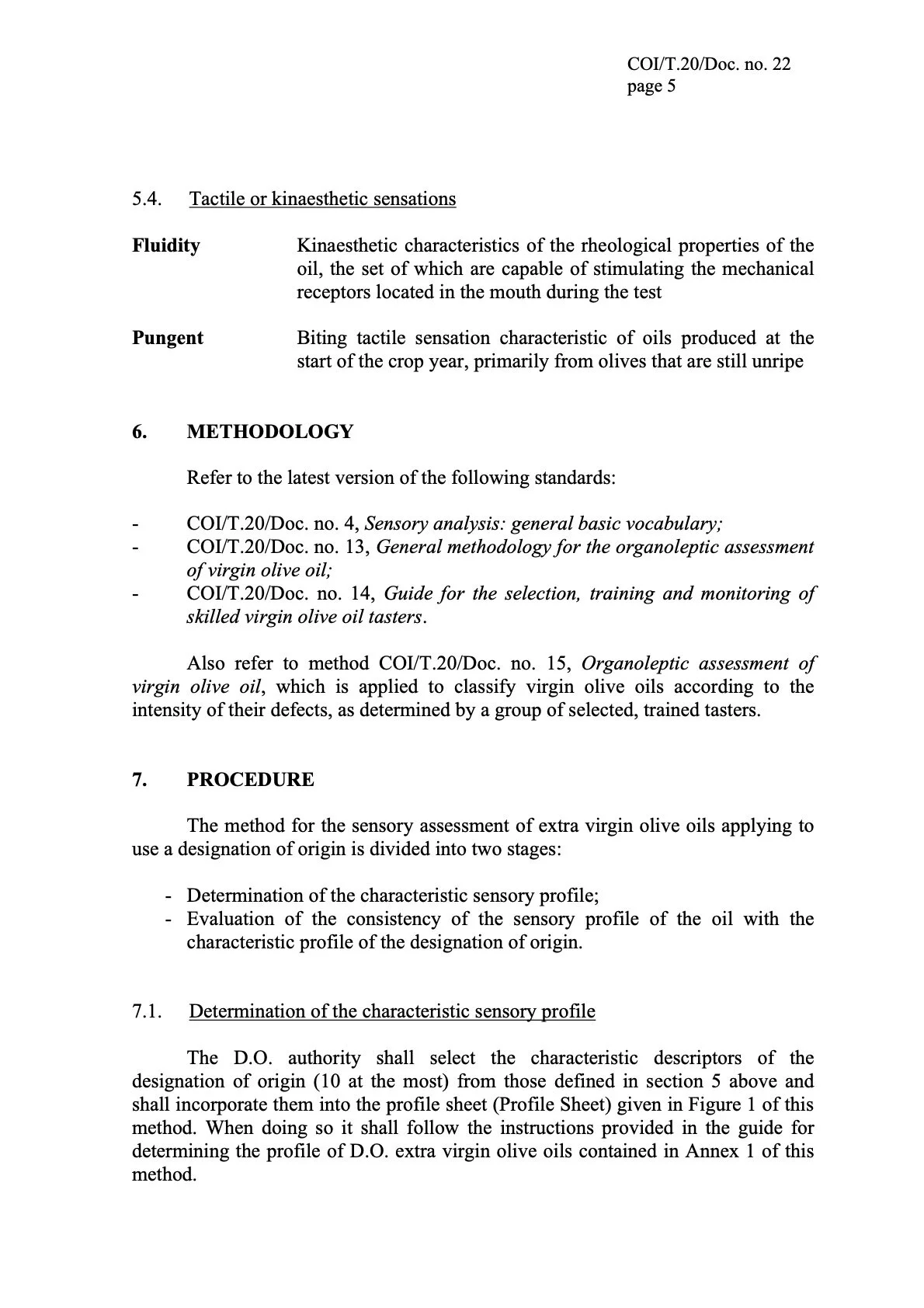

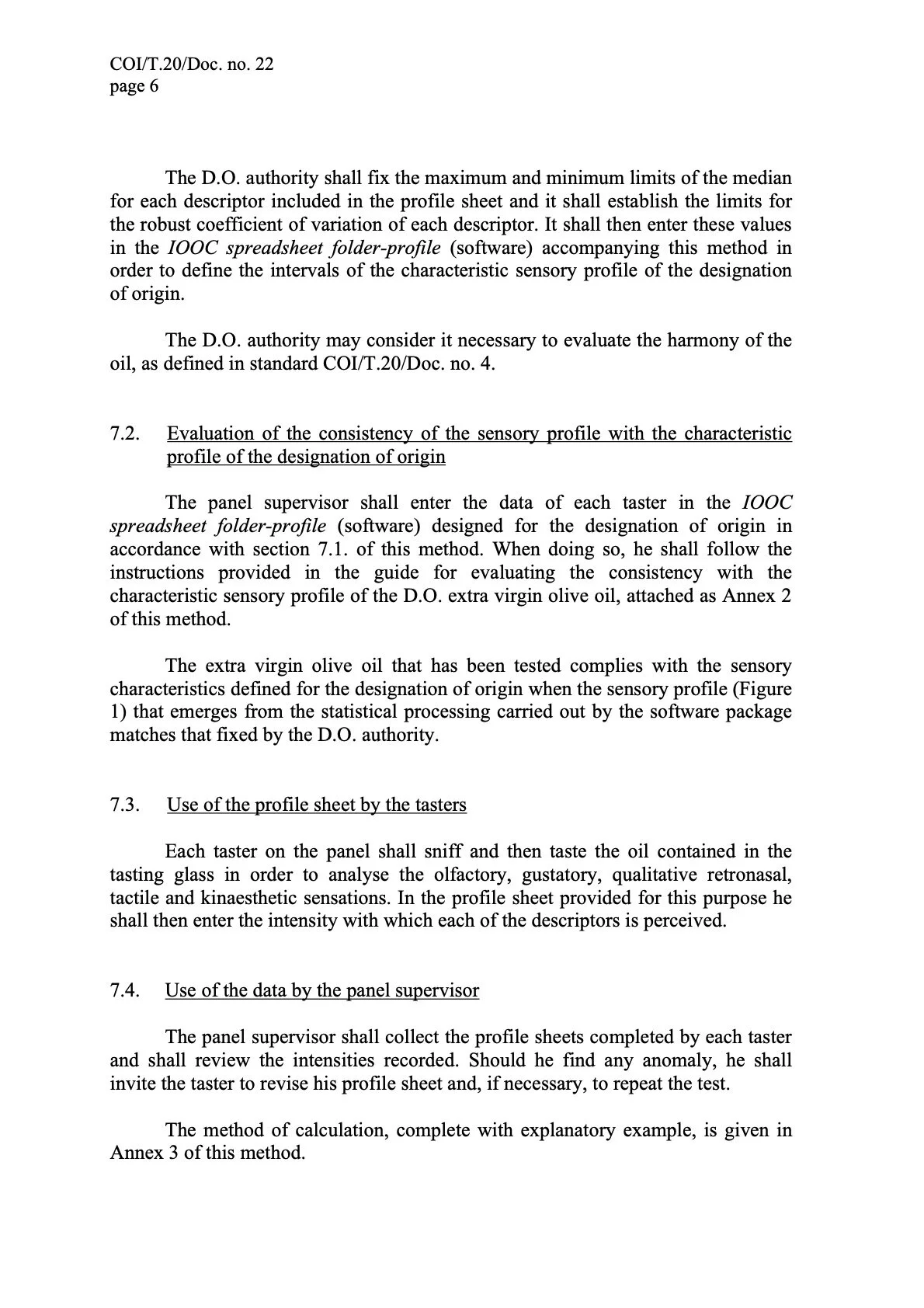

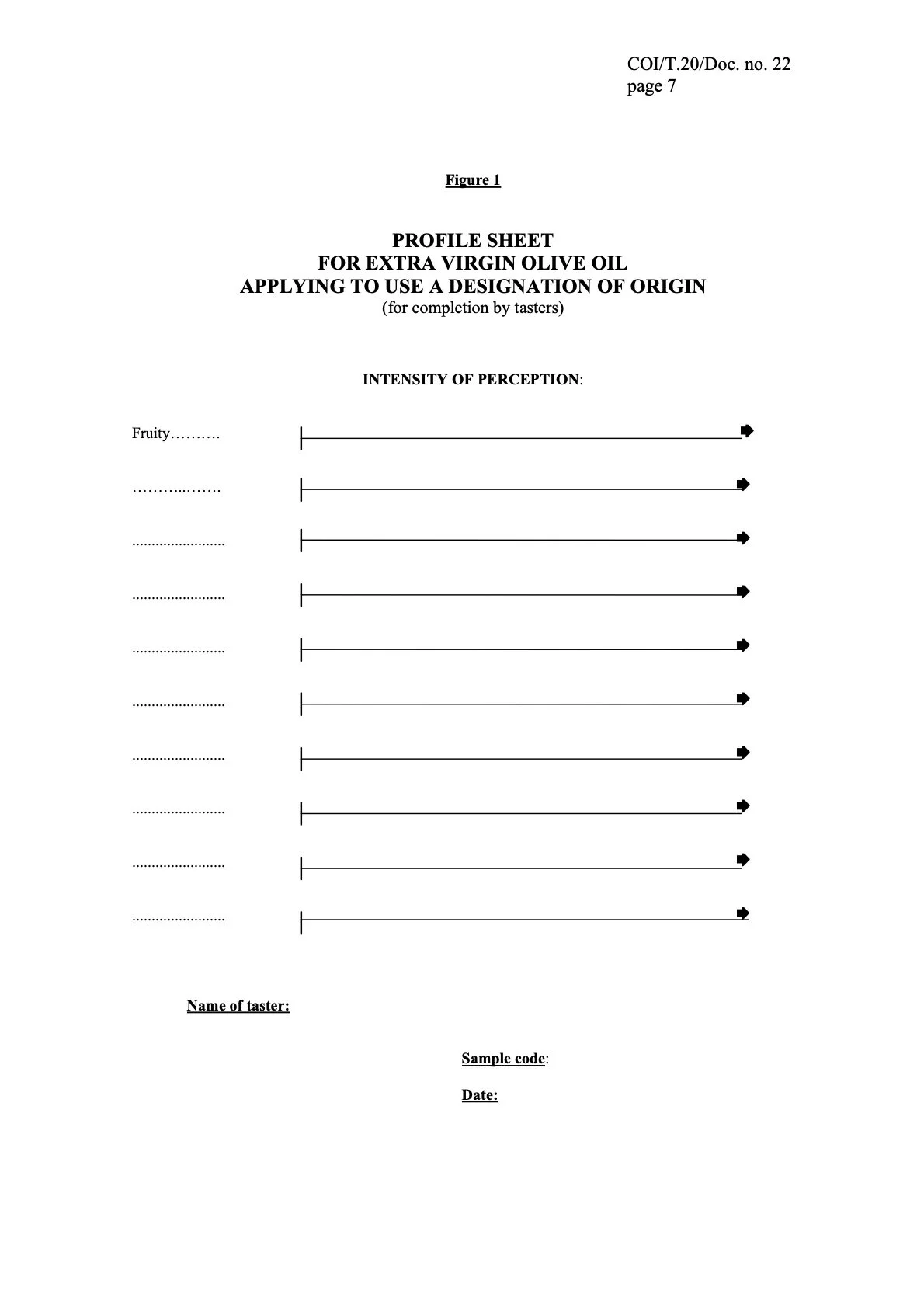

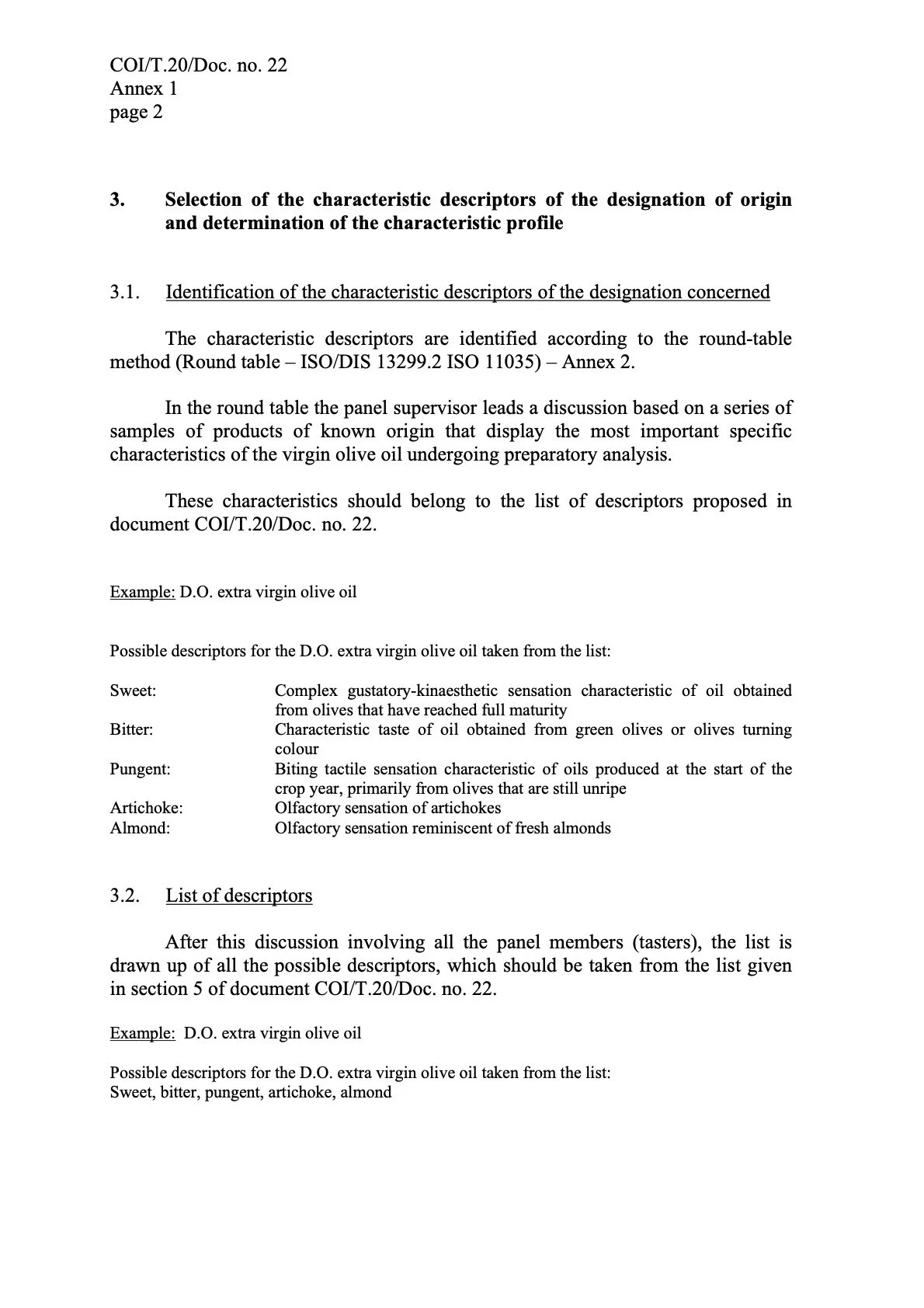

I will resume thoughts related to the above further down, such as in relating them to methodological stances, but first some comments on the excerpt above and images below. The excerpt presented above represents part of a resolution that specifies the internationally recognized method for evaluating extra virgin olive oils of particular designated origins; that is, for assessing such oils from clearly defined regions commonly labeled under the abbreviation of DOP. It thusly relates to regulatory and standardizing dimensions of sensory analysis of olive oils correspondingly (of) territories, and it occurs a much intriguing dimension for me to follow in making sense of the becoming of various olive oils in spatiotemporal terms. This document in its full version, among others like it, can be found at the website of the International Olive Council (link in references).

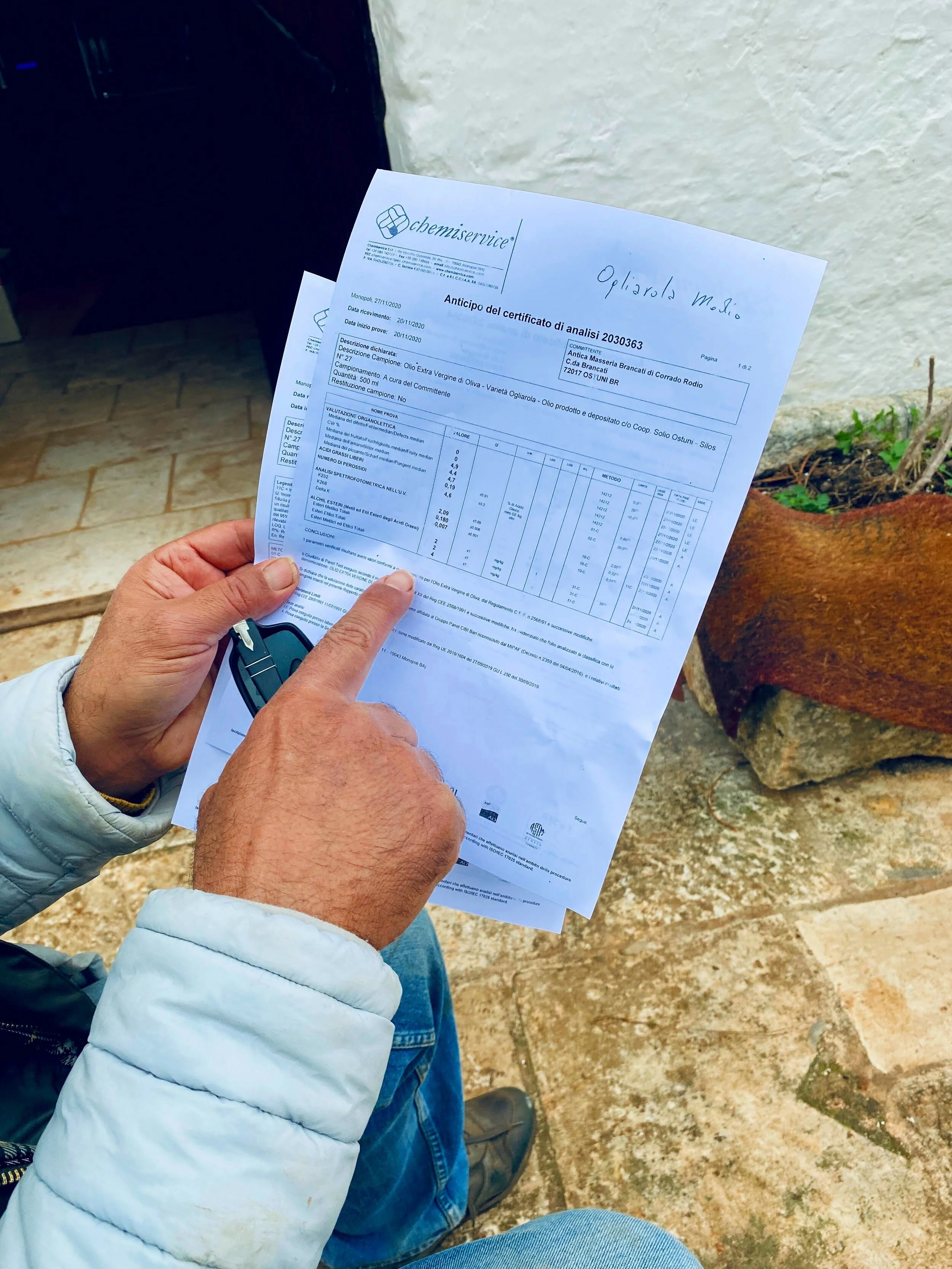

In the center of the picture featured to the left underneath, one may partake of two documents. These are certificates attesting the extra virgin quality of two olive oils produced by one of my key research collaborators, Corrado. The analyses supporting these certificates were carried out by a laboratory in Monopoli and include both chemical and organoleptic analysis of the oils; the significances of the analyses, the data detailed within them, specifications of how they were carried out and the relevance of having them done so to obtain a sort of authentication of these particular oils, were in detail explained to me by Corrado in the yard of his masseria in early December. The conversation was incredibly interesting and particularly valuable for me to understand the contextual scope of much of what I through my fieldwork up to that point and afterwards have experienced; many aspects of my research transpired evermore curious to further as a direct consequence of this fieldworking event; connections from previous fieldworking experiences and notes emerged in new lights. One such triggering aspect correlates for instance the extent of fraud oils present in the marketplace and the wish to enable a sort of authentication of olive oils of a certain quality; another to the fact that extra virgin olive oils must be void of any sensory detectable defects to be classified as EVOO. The latter was for me a previously unknown matter and I took it from Corrado’s emphasis on the significance of me becoming aware of how to distinguish negative attributes from positive ones—he urged me to develop a sense for what constitutes defects within olive oils, how such come about, and how they may be avoided within practices of olive growing and olive oil production—as an attest that this sensuous matter occurs highly important for evaluating not only oils, but also the work with which they become (one way or another). Keeping a clean mill is for example key to produce olive oils voided defects. Now, while I by no means am able to readily detect and distinguish particular defects such as trained practitioners can—them being able to specify and grade both kind and intensity of fustiness, rancidity, metallic attributes and more—I have as part of my research developed a more attentive awareness of some practices taking place (or not taking place) in the mills and become familiar with how such impact the sensory properties of the oils produced in the given environment. Simply put, and by way of relating my conversation with Corrado to specific fieldworking experiences, I realized the extent to which the meticulous cleaning at some pressing facilities, the void thereof in others, directly corresponds to the sensory experience of the oils produced within them. Furthermore, reflecting upon the fact that no one ever explained the constant cleaning to me as it took place, whereas many other things were explicitly detailed, not least in terms of oils being of the extra virgin quality, it occurred to me that the situated knowledge by which cleaning practices are carried out for many practitioners are practically sensed and routinely engaged. That is, they know through their embodied and emplaced ways of practically engaging extra virgin olive oil production that cleanliness is a prerequisite for obtaining such quality of oils. This knowledge goes by largely in doings through, much more so than in sayings, wherefore it is my understanding that these practitioners know not any defects through theory, but through practice; not through assigned evaluations, but through habitual undertakings of routine work; not through categorical distinctions framed in standardized profile sheets, but through instrumental workings with machineries.

Instrumental as cleaning practices occur performed in certain pressing facilities, instrumental occurs the training and practice to foster expertise for sensory evaluation of oils produced therein (whether performed by certified or otherwise experienced practitioners). As catalogued in the first paragraph of this post, qualifying as an olive oil taster of any degree takes much work and effort, and it requires a highly knowledgeable and perceptually skilled person to become one. I am miles away, with my thus far developed skills of evaluating olive oils—such as related to production techniques, olive cultivars, degrees of maturation and forces of water and oxygen that I through fieldwork encounters have become attuned to—not even close. It is fine though, for as the anthropologist that I am engaging this fieldwork, my purpose of familiarizing myself with the sensuous matters of olive oils rather revolves around my ability to ethnographically understand and critically analyze the situated skills of the practitioners with which my research is carried out, than to myself acquire the skills per se: to contextually explore particular perspectives and how such relates to the settings in which they take place, that is what I am trained to do, that is what I have spent years of schooling becoming skilled at, and that is where my line of expertise is founded. That noted, however, as much of my research occurs through a learn-by-doing mode of engagement, me participating in the work of the people who I conduct my research with, I have surely become more skilled and sensuously attuned also to the particular subject matters of study, such as to the production of olive oils, including recognition of various qualities thereof. It therefore occurs as such, that I, in unfolding and comprehending the practices and settings with which my research is concerned by means of an anthropological undertaking grounded in participant practice (Pink 2015: 6, 97-98), through time, space and practice have become habitually situated in the context of their occurrence, and thus, myself developed a much embodied and emplaced understanding for the things taking place. For, as I attune my body and rhythm, hearing and listening, tasting and savoring, touching and feeling, smelling and scenting, seeing and observing, I have learnt equally well about the subject matters at hand as about the sensor(e)alities through which they come about (cf. Pink 2015; Stoller 1987; van Ede 2009 for references on conducting sensuous scholarship).

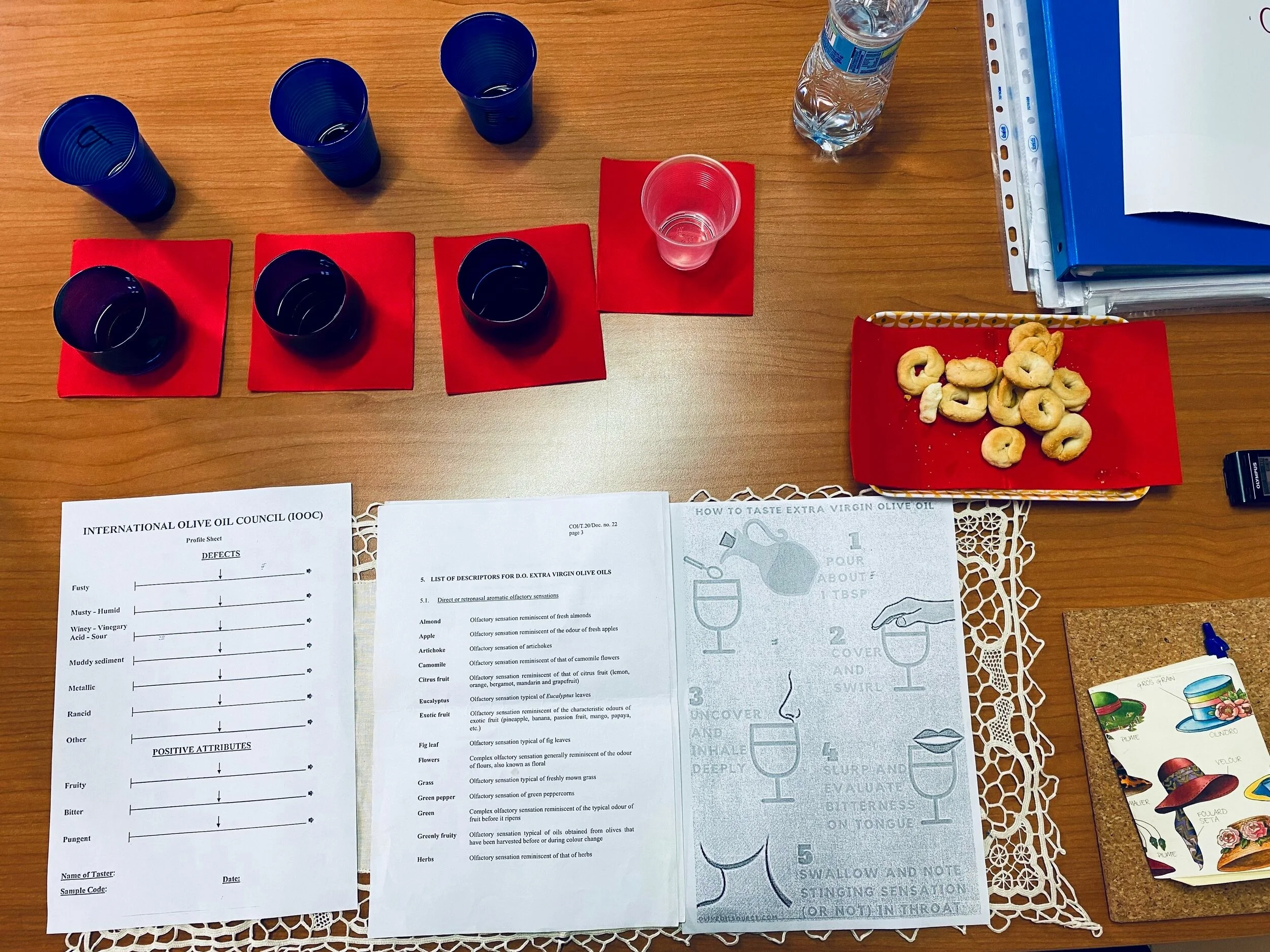

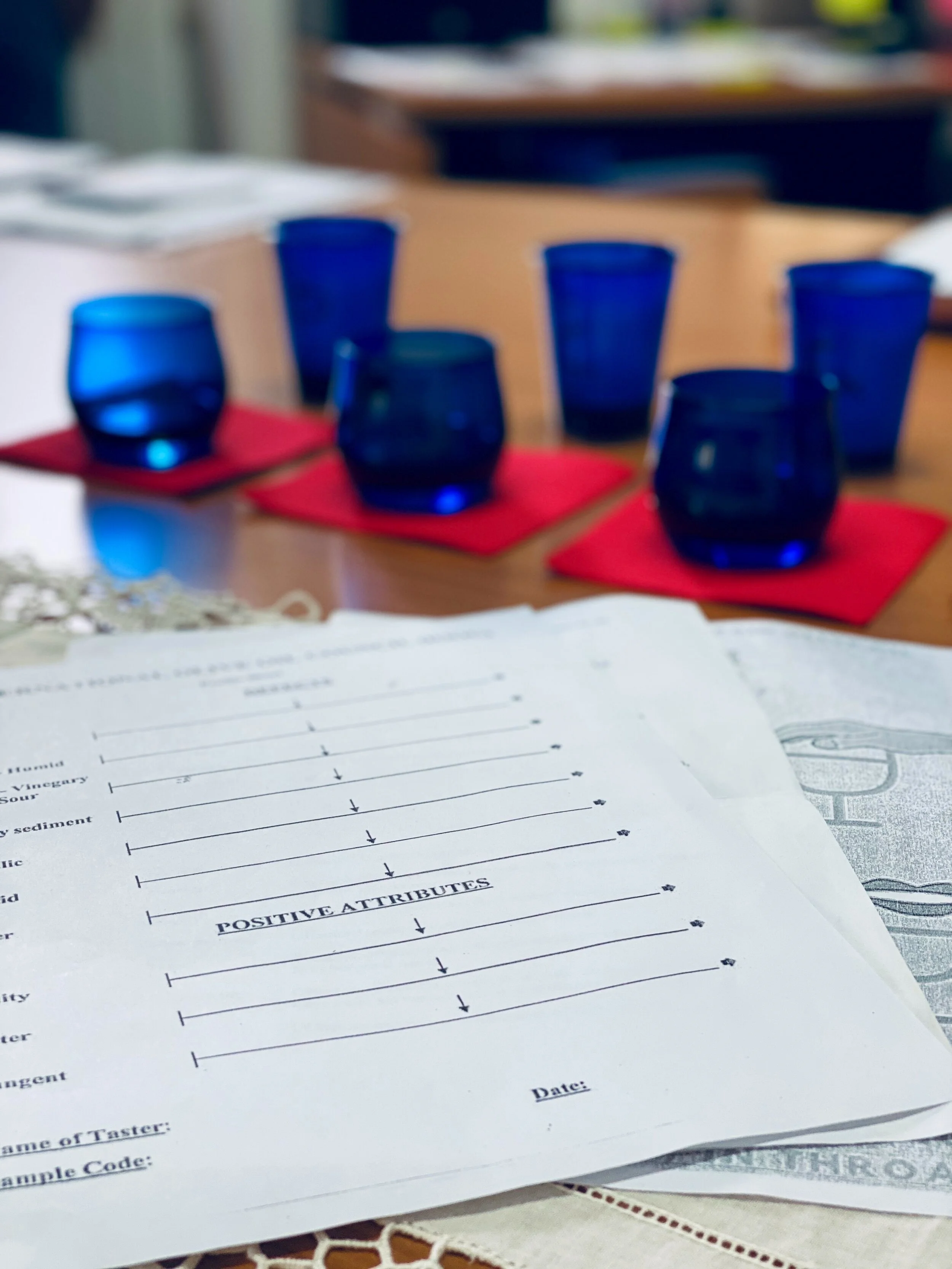

The above visualizes me for the very first time engaging some serious sensory tasting of olive oils. The visuals are from a tasting session taking place earlier this week with a research collaborator who, kindly enough, first level taster as he is, put together an instructive tasting session for me—the purpose of the tasting was for me to ethnographically explore and get a sense of the procedures through which sensory analysis occurs, not to train myself to become a taster—and they feature me undertaking the techniques through which sensory analysis occurs (i.e. with specific colored glasses so to rid biased evaluations related to color, and through a sort of forcefully and pulsatile inhaling of air sense the oil within the mouth and throat). I have many times during my fieldwork tasted oils and attempted to make some kind of sense of their profiles. It happened for instance on a regular basis during the extraction of olive oils in pressing facilities this past harvest season; it occurred, too, common practice as I visited producers in search for possible research collaborators during my prestudies. Those experiences accounted for, this was nonetheless the very first time where I got to put my collective understandings and gathered skills to practice, maybe even advance them a bit, push beyond the scope of personal preferences, and engaging the procedure of sensory analysis as a somewhat knowledgeable person. That is, as one experienced enough to evaluate the fruity, bitter and pungent character of one oil contra another, as one skillful enough to correlate the overall sensory profile of a given oil to the olive cultivar by which it was produced, as one cultivated enough to readily distinguish the one oil of lesser quality from the two of higher qualities, and as one practically engaged enough to critically probe the procedure and how it enacts categorical becomings of different oils and tastes. Happy as I was to feel that I actually had particular knowledge to sensuously put to practice, my expertise in the area only reaches so far. For instance, my ability evaluating oils is not refined enough to pinpoint specific descriptors, if at all, such as an adroit taster may, and this lack of skill on my behalf occurred very much apparent as Giorgio pointed out the grassy note of one of the oils. I had not sensed the grassy note at all, much less realized its dominant presence, not until mentioned by him, whereby I sensed it instantly and strongly. It was kind of an odd experience really, to be so familiar with a smell but unable to scent it, even with my nose stuck deeply into the glass, really trying to recognize particular notes. The experience kind of did not make sense to me at first, and I felt quite perplexed by the absence of sensation followed by the readily recognition thereof. However, as Giorgio reassuringly noted that reference frames are taught and learnt, through guidelines prompted and practical experience enforced, I got to think of the situatedness by which we all come to learn and know, and about the contextual associations that we more or less readily construe thereof: this was not a situation that I related to the scent of freshly cut grass, wherefor I probably did not scent such a smell, albeit the scent as such indeed occur familiar to me. Perhaps my experience had been different, had I, such as Giorgio, been trained to smell for the scent of grassy notes prior to this research encounter.

By way of wrapping up, alongside making righteous reference to the material of “How to Taste Extra Virgin Olive Oil“ included in the spread above, much material on how to carry out olive oil tasting, also as a fun family-friend activity, can be found on the following American website of Olive Oil Source: www.oliveoilsource.com. Happy Friday and joyful tasting, if deciding to engage such!

References

International Olive Oil Council. 2021. IOC Standards Methods and Guides. https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/what-we-do/chemistry-standardisation-unit/standards-and-methods/ (Accessed 2021-02-05).

Peri, Claudio (ed.). 2014. The Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Handbook. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publication Ltd.

Olive Oil Source. 2021. How to Taste. https://www.oliveoilsource.com/page/how-taste (Accessed 2021-02-10).

Monteleone, Erminio and Langstaff, Susan (eds.). 2014. Olive Oil Sensory Science. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Stoller, Paul. 1989. The Taste of Ethnographic Things. The Senses in Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press.

van Ede, Yolanda. 2009. Sensuous Anthropology: Sense and Sensibility and the Rehabilitation of skill. Anthropological Notebooks 15 (2): 61-75.